Memories of Detroit Tiger Baseball Announcer Ernie Harwell

Originally published on December 29, 2020

Memories of Detroit Tiger Baseball Announcer Ernie Harwell:

The late Ernie Harwell might be considered baseball's version of iconic Americana artist Norman Rockwell with a microphone.

There is little question that Ernie Harwell represented the best of his generation. He was kind, respectful, professional, and relatable. The people of Michigan were blessed to have such a man come to visit them in their leisure hours. In hindsight, he brought a soothing brand of entertainment that was perhaps better than the game itself.

Ten years after Ernie Harwell’s death, he still strikes a powerful chord of good feeling among Detroit Tiger fans. He has been off the radio for 15 years. Yet the warm feelings from his fans persist. I wanted to know what it was about Ernie that left such an indelible memory. Was it the chaos of current times that evoked such memories? Is it the wanting of some reassuring figure that lets us know all is well? Whatever the answer, this is clear, Ernie Harwell was a cultural icon in Michigan and perhaps in major league baseball. Ernie was Norman Rockwell with a microphone.

So, I decided to search for answers. I asked others how Ernie made them feel and included them in a podcast, and I wrote of my own experiences below. Here is what I learned:

CONVERSATION WITH JOURNALIST JACK LESSENBERRY

I talked with veteran Michigan journalist Jack Lessenberry, formerly with Michigan Public Radio. Jack was a long-time friend of Ernie Harwell and had covered his career when he worked at the Detroit News.

Arthur Busch: You knew Ernie Harwell.

Jack Lessenberry: I did. I first met him while I grew up listening to him like you. I first met him doing a magazine story on him in 1993. We got along; he always called me “The old professor.” I had the privilege of sitting in the broadcast booth with him a couple of times during games. And knew him for the rest of his life. He eventually got pancreatic cancer. He called me in 2009 to let me know about that. He did not want to see anybody in his last months. Afterward, we talked a couple of times on the phone. He was gracious. He was decent; He was very modest. What you saw is what you got.

I think he was the voice of baseball to millions of us in Michigan. It's still hard sometimes to think that he's not there anymore.

Arthur Busch: There was something about him. I have talked to several people in the Flint area, and they talk about this good feeling they had when they listened to him. There was a feeling that the whole world was well when they heard his voice.

Jack Lessenberry: He had all these marvelous stories. He kept all these on note cards. You know, reminding him about different stories and statistics about baseball.

Arthur Busch: Ernie would tell wonderful stories going back into the 1800s. He seemed to tell those stories as if he lived them.

Jack Lessenberry: Right, of course, he was born in 1918. He knew just about all the great people in baseball, including Connie Mack, and he knew Ty Cobb. I don’t think he knew Ty Cobb well, but he had interviewed him and introduced Cobb several times to stadium crowds. Leo Durocher got in a fight with Ernie, a physical fight where Durocher grabbed Ernie, and they tussled around for a while. You don't think of Ernie as a fighter. But Ernie knew virtually everybody who was important in baseball throughout the twentieth century.

Arthur Busch: That southern drawl, that silky southern drawl of Ernie’s, was a lure for my dad. That was an elixir for him.

Jack Lessenberry: I think you are onto something there, Arthur. I think that is true, and you know what, many famous baseball announcers have been from the south. In fact, Ernie worked briefly early in his career with Red Barber. He was the nationally famous voice of the Brooklyn Dodgers. He had a southern drawl. I think people liked it. It was not like a thick Cajun drawl that you had a hard time understanding. I like the word, silky that you used. He had this comforting, warm, down-home voice.

Arthur Busch: He had partnered up with George Kell for a period of time. Kell was the Baseball Hall of Fame baseball player, a 3rd baseman for the Detroit Tigers. He was from Arkansas.

Jack Lessenberry: Swifton, Arkansas.

Arthur Busch: That combination in the booth gave it an iced tea afternoon. You sit on the porch and listen to Ernie & George.

Jack Lessenberry: Ironically, George Kell is why Ernie Harwell ended up in Detroit. I don't know that they were especially close. In 1959, the announcer had been Van Patrick. You may or may not remember him. He was on channel 4 in Detroit and had a conflict with an advertiser. George Kell suggested, why don't you look at this guy Ernie Harwell? At that time, Ernie was the voice of the Baltimore Orioles. So, one thing led to another, and Ernie Harwell came to Detroit, starting with the 1960 season, as an announcer. Except for the infamous interlude where he was fired for a couple of years by WJR and the Tigers Bo Schembechler, he was on the air until I believe, 2002, when he finally retired.

Arthur Busch: These guys (Harwell and Kell) were funny because of how they would talk about the players, especially Ernie. There was a period in which he described what jobs players had during the off-season. Funny as heck! I never envisioned the guy sitting on second base sweeping the floor at the local grocery.

Jack Lessenberry: If you remember Richie Hebner, he dug graves. He was a grave digger in the off-season.

Arthur Busch: Oh lord!

Jack Lessenberry: People did not realize that Ernie Harwell was not just an announcer. He was an integral part of the Detroit psyche. By that time, he had become the background voice of baseball. Everybody loved his voice. Even people who didn't love baseball loved Ernie Harwell. You thought about summer and thought about a picnic. This was way before i-pods, way before Alexa, you have a transistor radio out there somewhere, and you hear Ernie Harwell’s voice. He had the ability even if the team was terrible and the Tigers were losing to the Yankees 12-2 in the third inning. He had the ability to make you still care about the game and listen to it. That is so because Ernie Harwell is not just the play-by-play announcer; he had these wonderful stories and brought you into the game. He did one thing that was not accurate. He would say the ball was hit into the stands and say, “that was caught by a man from Flint, or that a lady caught from Flat Rock.” Of course, he made that up. When I was young, I wondered how he knew that stuff. Of course, (he didn't know where they were from) but people liked hearing this.

Arthur Busch: He understood the tempo of the baseball game, and he understood something that not many people, including me, get. He understood the value of silence. Silence is golden.

Jack Lessenberry: I think you're right. He knew how to use silence; he knew how to use words, and he was completely authentic.

Arthur Busch: I wanted to ask about your impressions of all these euphemisms Ernie Harwell used. He had these sayings and coined all these phrases that still live in the memories and hearts of his fans, Tiger fans everywhere. Did you have a favorite one?

Jack Lessenberry: “He stood there like a house by the side of the road.” And of course, if it is a home run, “It is long gone,” he adopted that later. But remember, early on, he would say when somebody struck out, “he stood there like a house by the side of the road.” What was your favorite one?

Arthur Busch: I like the one where he says, “He got caught doing excessive window shopping.”

Jack Lessenberry: That's right. That's for a called strikeout. That's exactly right.

Arthur Busch: Yeah, and another one of them, I liked, “he stood there like the house by the side of the road” I adopted as my own over the years.

Jack Lessenberry: Good! He'd be pleased about that.

Arthur Busch: Ernie Harwell had a stutter when he was young.

Jack Lessenberry: Exactly. He had quite a stutter as a child. He worked hard on it. He mentioned that in his (Baseball) Hall of Fame speech when he was inducted. He said he was “born tongue-tied, but thanks to the grace of god, I am not tongue-tied anymore.” Although he said, he felt tongue-tied at that moment. He just worked at it. He worked hard at it. He grew up in a poor family in rural Georgia and worked hard to overcome to make something of himself. He was very religious, but he wasn't obnoxious about it. If you weren't religious, he didn't try to convert you. He didn't try to proselytize, but it was a big part of his life. He was a very modest man. Once I was doing a story about World War II and was looking at some pictures of cement and landing craft on Wake Island.

I said to him, “This looks like you. He said he was a marine in World War II and saw heavy combat. He never talked about that. He was a fascinating, fascinating man.

Arthur Busch: Some have attributed his most famous poetry reading, which isn’t a poem at all; it’s a scripture verse.

Jack Lessenberry: The “Voice of the Turtle”

Arthur Busch: “The house by the side of the road” phrase as it turns out Ernie worked thru that stutter by reading poems. And he read other poems. Now, Ernie, to his credit, besides giving us a little white lie about who caught the ball and where they were from, modified the “Voice of the Turtle” to suit his purposes. Were you aware of that?

Jack Lessenberry: No. I don't think I was.

Arthur Busch: You will find that turtles don't speak, so it was turtle doves, that is what the scripture says. How did it make you feel when Ernie read that verse?

Jack Lessenberry: Like it was officially sprung on opening day. Everybody loves Opening Day. I remember hearing him say that on Opening Day in April 1966, they opened against the Yankees, the Tigers won 2-1, and Joe Pepitone hit a home run. Now don't ask me where I put my keys. Don't ask me what I ate for breakfast yesterday, but I remember that from April 12, 1966. So that shows how powerful memories of somebody like Ernie Harwell can create and evoke in people.

Arthur Busch: Ernie was a broadcaster during some of Detroit's most tumultuous, turbulent times. That was during the 1960s, especially 1967 and 1968. Maybe you have some comment on this, but it seemed like he was the voice that brought a certain calm. He brought people together not only around the game. His voice made us think that everything was going to be okay. He made us feel we were all together.

Jack Lessenberry: The day the riots started, he was broadcasting. They told him not to mention it. They told him not to mention it because you could see the smoke, things like that. It hadn't reached its full height. That was on Sunday, and I think July 24, 1967. Baseball is still here. He has some qualms about that. He didn't know quite what to do. They told him don't mention it, and he didn’t.

Arthur Busch: You think we'll ever see somebody else down the road that has the same skill as this guy?

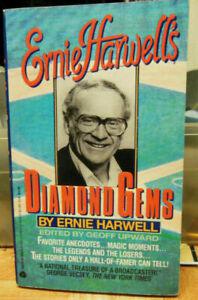

Jack Lessenberry: He was a very conventional as well as a very modern man for his time. I just hope people remember him. He wrote several books, “Diamond Gems” is a collection of his anecdotes, and “Tune the Baseball” was his first book. While I think we'll see somebody else that is great but different. I know a fair amount about the past and a fair amount about the present. I learned a long time ago that I couldn't predict the future. But I hope so. He would like that and very much that baseball will continue to be our national game. People should still read those (books). Get some tapes if you have any ambitions of being a broadcast announcer, especially for sports, and want to hear what the best sounds like. They are available on CD. Listen to how Ernie Harwell did it because nobody ever did it better.

Arthur Busch: Jack Lessenberry, Thanks for joining me on Radio. Free Flint.

Ernie Harwell & Me: Ernie Harwell Was Part of Our Family

Ernie Harwell was part of my earliest memories of my home in Flint. His soft Georgia drawl echoed across the kitchen in the evenings when the Detroit Tigers were playing America’s game. My dad, a southerner, loved listening to Ernie while smoking cigarettes and smiling at his homespun one-liners. Soon my dad would smile as Ernie gleefully announced, “IT’S LONG GONE! WAY BACK IN THE CENTER FIELD BLEACHERS! Stormin’ Norman Cash has hit it a mile, Ernie reprised. There was something about that voice, the language he used, and the pictures he painted with words that were soothing. It was as if he was painting pictures of America’s pastime like Norman Rockwell, but Ernie did so with a microphone instead.

Looking back at the iconic Ernie Harwell, he also seemed to bring something else Americans cherished: Unity of Purpose. We were all for the home team, the DEEETROIT TIGERS. He sounded us with his joy of inviting all of us into the game of baseball. When a batter would hit a “foul pitch,” as Ernie was fond of saying, he would declare the man who got the souvenir baseball hailed from Durand or Flushing or West Branch or Saginaw just “one-handed” the ball. I always waited for Ernie to announce Flint, Clio, or Grand Blanc. That was Ernie’s way of using the booming 50,000 watts of the WJR radio signal to unite the people of Michigan. He wanted us to know that Detroit Tiger fans were everywhere, especially at Tiger Stadium. Ernie even did this for road games in faraway places like Seattle.

While growing up as a kid in Flint, I believed that Ernie knew everyone in the old Tiger Stadium. I trusted Ernie Harwell and everything he said about baseball. As I grew older, I realized Ernie did not know exactly where everyone at the ballpark “hailed” from, as he would say. But even knowing that, I still loved and trusted him.

Ernie brought us together as a family. We loved baseball, and a good part was Ernie Harwell and George Kell. Kell was a former Detroit Tiger Star who played third base for the Tigers in the 1950s. He was from Arkansas. When Ernie was paired with Kell, you felt like you were on the front porch in Macon, Jonesboro, or Atlanta, complete with the iced tea and your ears glued to the radio. My dad especially loved George Kell as he owned a car dealership nearby my father’s hometown of Paragould, Arkansas.

There was something about how Ernie Harwell explained the world that made me believe everything was all good. Ernie took dad, mom, and me far away from the chaos of the 1960s to a calm place where there were heroes and dreams. Ernie took us through the pennant races in 1967 when the Tigers came up short to the Boston Red Socks and then to the 1968 championship year. His voice of calm and togetherness was in stark contrast to the Detroit around us with its unrest and rioting.

Ernie Harwell was more than a sports broadcaster; he was a true cultural icon and perhaps part of the psyche of Detroit and Flint. His many decades announcing baseball gave him an audience that appreciated his manners (everyone was Mister or Mrs.), and his pleasing kindness was afforded to everyone, even the opposition. His method and mannerisms never belied his entertainment value. He spun lines like this when 30-game winning pitcher Dennis McLain was on the mound for the Tigers, “he kicks and deals” to the batter.

There will never be another Ernie Harwell. Perhaps like no other associated with major league baseball, he lives in our hearts.