WEBVTT

00:00:00.000 --> 00:00:01.679

You're listening to the Mitten Channel.

00:00:01.840 --> 00:00:04.400

Michigan Stories, Michigan Voices.

00:00:13.279 --> 00:00:16.079

Hello, my name is Sarah James with the Mitten Channel.

00:00:16.239 --> 00:00:17.679

Thank you for listening to us today.

00:00:17.839 --> 00:00:30.719

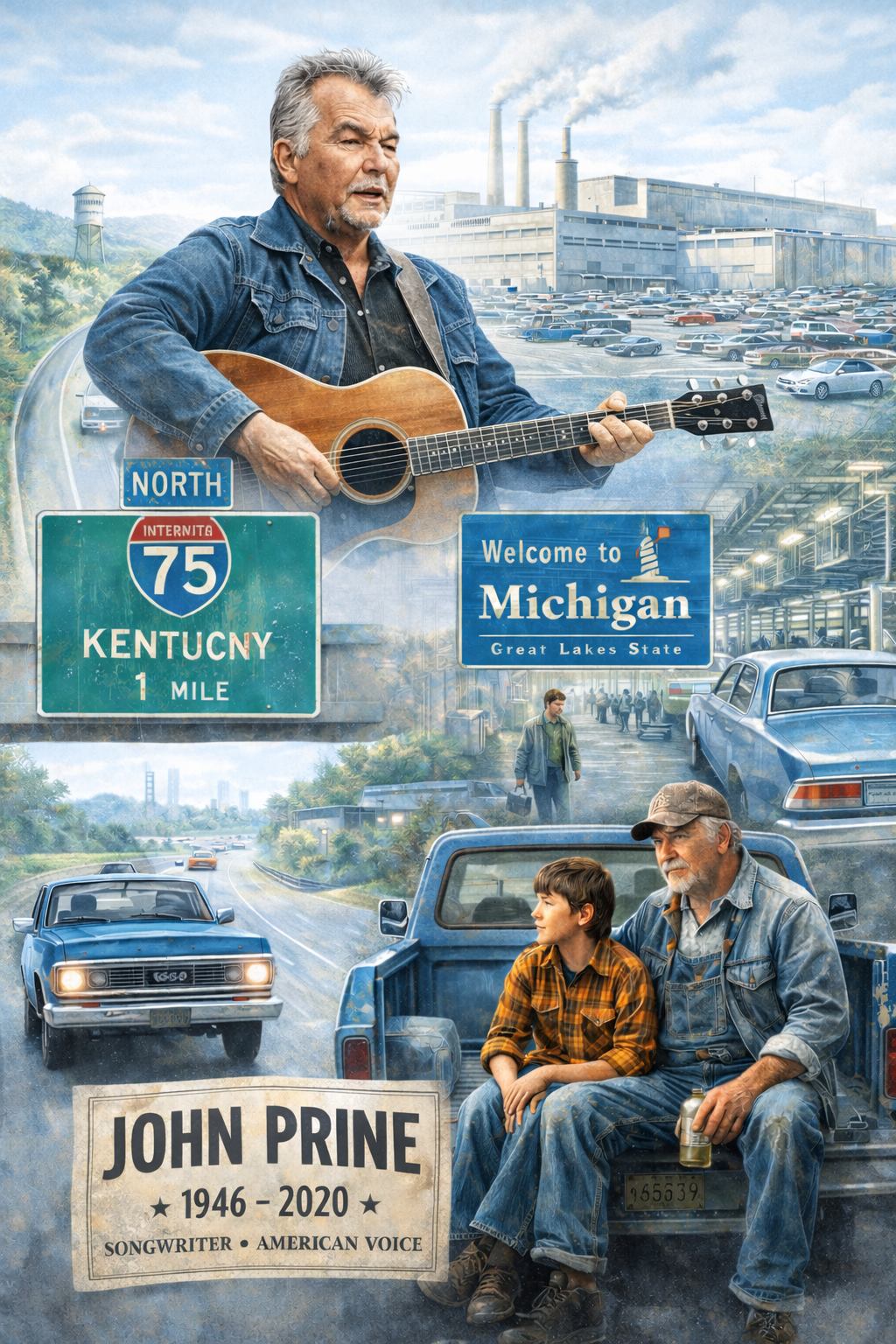

Our podcast today is a feature on the life of John Prine, the revered singer-songwriter from Maywood, Illinois, who died on April 7, 2020, in Nashville at the age of 73, from complications related to COVID-19.

00:00:30.879 --> 00:00:35.920

We want to discuss the significance of John Prine's work was to the American working class.

00:00:36.159 --> 00:00:39.119

First, however, let's share his family history and background.

00:00:39.359 --> 00:00:43.359

John was raised in a working class family, with roots in western Kentucky.

00:00:43.520 --> 00:00:50.320

He went from carrying mail on suburban Chicago routes to becoming one of the most influential American songwriters of his generation.

00:00:50.560 --> 00:01:01.439

Praised by contemporaries and critics alike as a kind of Mark Twain of modern songwriting, he was celebrated for plain-spoken stories that found humor and grace in the lives of ordinary people.

00:01:01.679 --> 00:01:14.959

Over a five-decade career, he released a string of acclaimed albums, earned multiple Grammy Awards and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy, and, shortly after his death, was named Honorary Poet Laureate of Illinois.

00:01:15.120 --> 00:01:25.359

For coal towns and factory towns across the Midwest and South, the news of his passing felt less like the loss of a star, and more like the loss of a familiar neighbor whose songs had been there all along.

00:01:25.519 --> 00:01:30.239

He was born into a family that had already made the classic Southern to Midwest migrant journey.

00:01:30.400 --> 00:01:42.159

His parents were natives of rural western Kentucky, from around Paradise and Muhlenburg County, who moved north to Maywood, Illinois in the 1930s to escape coal country hardship and find steadier industrial work.

00:01:42.400 --> 00:01:50.000

He was the third of four sons raised in Maywood, a working-class suburb west of Chicago where his father worked as a machinist and tulin dye maker.

00:01:50.239 --> 00:01:55.760

Even after the move, the family went back to Kentucky often, visiting relatives near Paradise.

00:01:55.920 --> 00:02:05.120

The music, language, and stories from those trips left a lasting mark on Prine's imagination, and later became the emotional landscape of songs like Paradise.

00:02:05.280 --> 00:02:18.240

Growing up in Maywood, he absorbed both blue-collar Chicago life and the southern culture his parents carried with them, a dual identity that let him write convincingly about factory towns, coal camps, and small town porches alike.

00:02:18.560 --> 00:02:20.080

Thank you, Sarah, for that introduction.

00:02:20.240 --> 00:02:23.039

This is Ellis Vance, also a reporter for the Mitten Channel.

00:02:23.199 --> 00:02:26.080

We will now turn to the places where John Pryan called home.

00:02:26.240 --> 00:02:27.680

That geography matters.

00:02:27.840 --> 00:02:36.639

Maywood felt, in many ways, like the northern end of the same migrant road that carried Kentucky and Tennessee families into Flint, Detroit, Lansing, and Toledo.

00:02:36.800 --> 00:02:52.080

The same people who left Muhlenberg County and neighboring hollers for industrial suburbs around Chicago also sent cousins and siblings along Dixie Highway and US 25-M54 into Michigan's auto belt, chasing a union wage at GM, Ford, and Chrysler.

00:02:52.240 --> 00:03:02.719

Prine's family story sits squarely inside that stream, which is why his songs sound at home in both coal country and in the driveways and porches of factory neighborhoods hundreds of miles north.

00:03:02.879 --> 00:03:06.080

From the beginning, Prine's writing did more than entertain.

00:03:06.240 --> 00:03:12.560

His songs told the history of this migration and the people who lived it, people whose story rarely appeared in official histories.

00:03:12.719 --> 00:03:18.479

One of his most enduring pieces, Paradise, looks back toward his parents' world in western Kentucky.

00:03:18.639 --> 00:03:34.719

In the song he recalls traveling, down to western Kentucky where my parents were born, to a backwards old town, remembered so often that, the memory is almost like a war, and a father who can no longer take his child back to Muhlenberg County, down by the Green River, where paradise once stood, because Mr.

00:03:34.800 --> 00:03:37.039

Peabody's coal train has hauled it all away.

00:03:37.280 --> 00:03:51.840

It is a simple story on its face, but underneath it lies a record of what industrial extraction did to a place: strip mines tearing up hillsides, a giant coal-fired plant rising over the river, homes and businesses bought out and leveled, until only a cemetery on a hill remained.

00:03:52.080 --> 00:03:59.520

For families who came north from coal country, paradise became more than a protest song or a nostalgic memory, it became a compact family history.

00:03:59.759 --> 00:04:08.159

It captured the experience of seeing a hometown literally erased by a company's machines, then carrying that erasure with you into a new life in a factory city.

00:04:08.400 --> 00:04:19.279

The people who later turned up on streets in Flint, Detroit, and Lansing, people with parents from Kentucky, Tennessee, or Arkansas, could hear in Paradise the story of why their families had left in the first place.

00:04:19.519 --> 00:04:24.639

The memory of a town that no longer existed traveled with them, and Prine gave that memory a melody.

00:04:24.959 --> 00:04:32.240

Let's look more deeply into what Prime's songwriting captured and where it fits culturally into what is known as Americana music.

00:04:32.399 --> 00:04:40.319

If Paradise explains why so many left, Sam Stone explains what happened to some of those who went away to war and came back broken.

00:04:40.560 --> 00:04:46.000

Sam Stone is one of the most powerful songs ever written about America's involvement in the Vietnam War.

00:04:46.160 --> 00:04:55.600

It tells the story of a veteran who returns home with shrapnel in his leg and trauma in his head, turns to drugs, and spirals downward while his family looks on, helpless.

00:04:55.759 --> 00:05:05.759

The haunting line, There's a hole in Daddy's Arm where all the money goes, says more in a few words about addiction, despair, and the failure of institutions than many books do.

00:05:06.000 --> 00:05:17.600

It is not just about one man, it is about a whole class of young men, many from working-class families in coal towns and factory neighborhoods, who were sent to fight and then returned to communities that did not have the tools to help them.

00:05:17.759 --> 00:05:22.639

In places like Flint, Detroit, and their suburbs, that story was painfully familiar.

00:05:22.800 --> 00:05:34.399

These cities sent disproportionate numbers of sons to Vietnam, kids whose parents had left the South for auto work, and who now found themselves back on front porches and in small living rooms, watching a son they barely recognized.

00:05:34.639 --> 00:05:41.680

Prine's veteran is not an abstraction, he is the guy from the block, or the cousin who used to work second shift at the plant before he enlisted.

00:05:41.839 --> 00:05:48.480

By putting Sam Stone's story into a plain-spoken ballad, Prine wrote down a grievance those families often carried in silence.

00:05:48.720 --> 00:05:55.199

They had done what was asked of them, left home for work, sent their children to war, and the country had not kept its end of the bargain.

00:05:55.360 --> 00:06:00.399

Where Sam Stone looks at the cost of war, hello in there, turns its attention to the elders left behind.

00:06:00.560 --> 00:06:06.480

It is a quiet song about aging and loneliness that needs no anger, just a gentle question, hello in there, hello.

00:06:06.639 --> 00:06:14.879

The verses describe an older couple, whose children have moved away, whose friends have died, whose days are filled with small routines and long silences.

00:06:15.040 --> 00:06:18.720

The chorus is a simple plea not to walk past them as if they were invisible.

00:06:18.959 --> 00:06:21.839

The power of the song is that it never raises its voice.

00:06:22.000 --> 00:06:26.879

It simply insists that there is still a person in there, behind the wrinkles and the empty porch.

00:06:27.040 --> 00:06:33.360

Now back to Ellis to discuss the linkages and values brought by Southern migrants to places like Michigan from Kentucky.

00:06:33.600 --> 00:06:37.759

Listeners from both the South and the industrial north recognize those elders.

00:06:37.920 --> 00:06:44.319

In Kentucky and Tennessee, grandparents gathered on front porches to watch the road, sip iced tea, and talk with neighbors.

00:06:44.480 --> 00:06:53.439

In Flint, Detroit, and other factory towns, similar scenes unfolded on small front steps and in tiny yards next to chain-link fences and smokestacks.

00:06:53.600 --> 00:07:02.079

The older generation had never expected to live in the north, much less in the shadow of auto plants, but there they were, rocking in chairs as the traffic went by.

00:07:02.399 --> 00:07:10.160

Hello in there captures their loneliness and their quiet dignity, the sense of having uprooted themselves only to end up in a place that was never quite meant to be home.

00:07:10.399 --> 00:07:18.879

Prine's songs did not only describe hardship, they also revealed a moral code, a way his people understood loyalty, patriotism, and duty to one another.

00:07:19.120 --> 00:07:26.959

Grandpa was a Carpenter, is a deceptively simple song about a man who hammered nails and planks and voted for Eisenhower because Lincoln won the war.

00:07:27.120 --> 00:07:29.519

In a few lines it sketches a whole worldview.

00:07:29.759 --> 00:07:40.480

Here is a man whose identity is bound up with his work, who sees his political choices through the lens of history handed down in family stories, and who takes for granted that you honor the country that, in his view, saved the Union.

00:07:40.720 --> 00:07:42.319

It is not a policy statement.

00:07:42.480 --> 00:07:46.800

It is a picture of how a certain kind of working-class patriotism feels from the inside.

00:07:47.040 --> 00:07:59.680

That mix of values, hard work, loyalty to family, pride in country as they understand it, a belief in doing your part, traveled north in the same cars and buses that carried these families from Kentucky and Tennessee into Illinois and Michigan.

00:07:59.839 --> 00:08:03.279

For the people in Prine's songs, patriotism was not abstract.

00:08:03.519 --> 00:08:09.839

It meant serving in the military, paying taxes, standing for the flag, and showing up at the plant day after day.

00:08:10.079 --> 00:08:19.040

In return, they expected a measure of security and respect, a job that could support a family, a neighborhood where people looked out for one another, a country that would not forget them.

00:08:19.279 --> 00:08:33.759

Those expectations rode with them on the long journey north, from Muhlenberg County to Maywood, from small towns along the Green River, to neighborhoods on Dixie Highway and the streets of Flint, Detroit, and Lansing, where whole blocks of migrants learn to stick together when no one else would.

00:08:34.000 --> 00:08:37.840

Now back to Sarah to sum up the Mitten Channel's ode to John Prying.

00:08:38.159 --> 00:08:47.919

Taken together, these songs Paradise, Sam Stone, Hello in There, Grandpa Was a Carpenter, and many others, form more than a catalog of characters.

00:08:48.080 --> 00:08:53.120

They are a long ledger of what a particular class of Americans lost and what they held on to.

00:08:53.279 --> 00:09:06.240

They lost towns erased by strip mining and power plants, suns damaged by war, elderly people marooned in places they never meant to die, and a sense of trust that the institutions above them would keep their promises.

00:09:06.399 --> 00:09:14.240

They held on to a stubborn code: work hard, stand by your people, honor your history, and try to be decent in a world that often is not.

00:09:14.480 --> 00:09:23.679

Prine's genius was to write that history and that code, in a language so plain that anyone could sing along with it, and, in singing, recognize themselves.

00:09:23.919 --> 00:09:32.559

When he died, the official tributes focused on the craft, his wordplay, his humor, his influence on other songwriters, and all of that was true.

00:09:32.799 --> 00:09:40.000

But for the families who had come up the Hillbilly Highway, out of coal country and into factory towns, his death felt like something more.

00:09:40.240 --> 00:09:49.519

It felt like losing the one person who had been quietly keeping their minutes all along, writing down their stories in three-minute songs no historian ever thought to consult.

00:09:49.679 --> 00:10:03.120

His music reached across state lines and decades, speaking to the people who left Kentucky and Tennessee and Arkansas for Illinois and Michigan, who found themselves in Maywood or Flint, or Detroit, trying to make a life in a different hard place.

00:10:03.360 --> 00:10:07.919

This podcast is both an obituary and an ode, but it is also an introduction.

00:10:08.159 --> 00:10:17.440

John Prine's songs were never just about one town or one boy from Maywood, they were about a whole migration and a whole class of people trying to carry home with them into a new world.

00:10:17.600 --> 00:10:29.440

To understand what was lost when we lost him, it is necessary to look more closely at the world he came from, the coal towns that vanished, the highways that carried people north, and the factory cities where they tried to start over.

00:10:29.679 --> 00:10:31.039

Thank you for joining us today.

00:10:31.200 --> 00:10:32.320

Goodbye.